Natasha Jen is a world-renowned designer, thinker, and educator, and a partner at Pentagram’s NYC office. She has a reputation for compelling and outstanding work and has won numerous awards and accolades. Not afraid to speak her mind and challenge the status quo, she regularly gives talks and guest lectures, including the ground breaking ‘Design Thinking is Bullsh*t’ at the Adobe 99u conference in 2018.

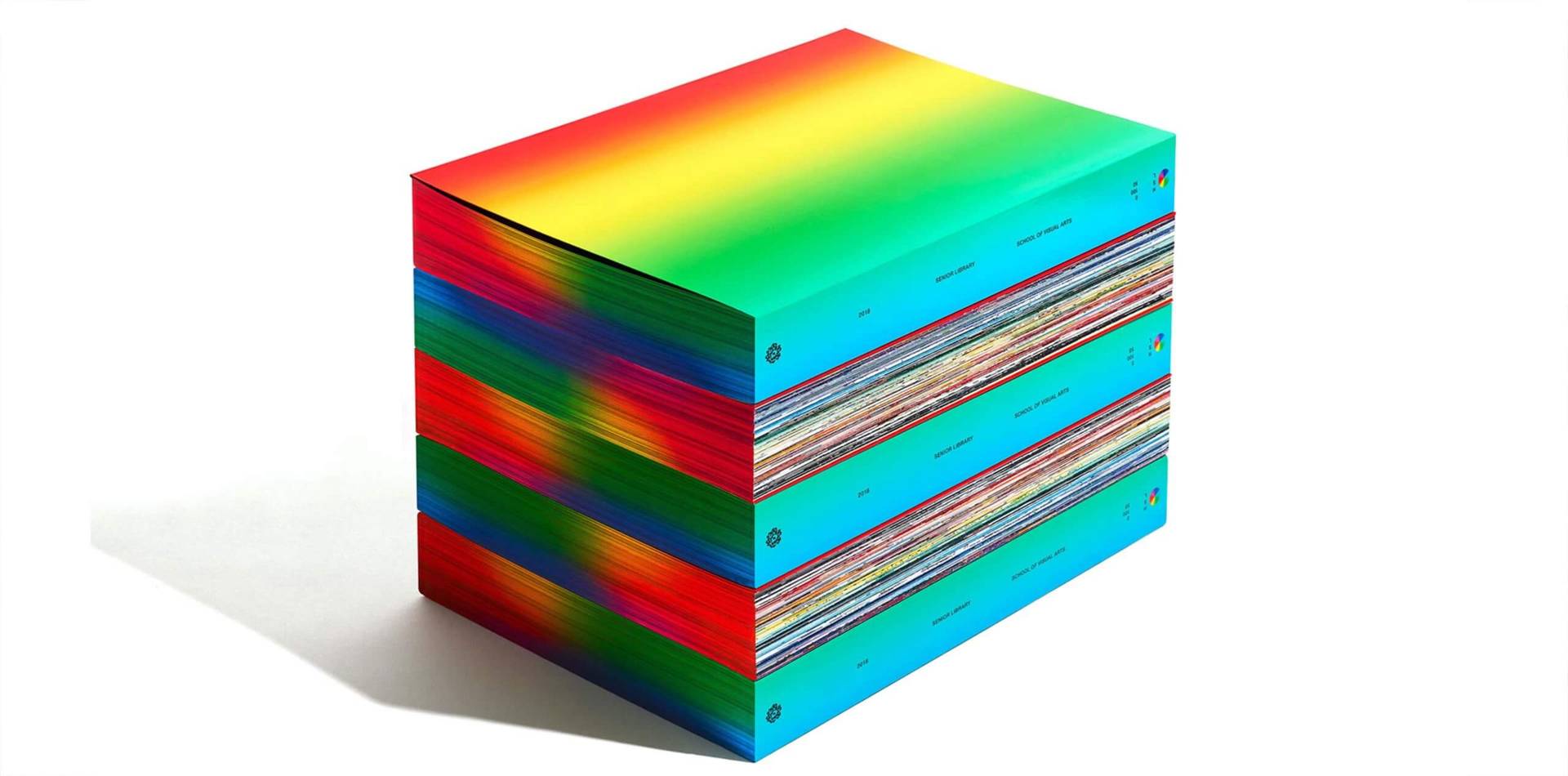

Having realized early on that she wanted a career in design, Natasha interned throughout her time in college and after graduating from the School of Visual Arts quickly landed a job at Base Design in New York. Early in her career, she gained experience at various multi-disciplinary studios and a strategy company, where she honed her business skills, before setting up her own studio N Jen Works in 2010. In 2012, Natasha joined Pentagram NYC as a partner, where she has continued to develop her impressive career to date.

Natasha doesn’t see herself as a manager in the traditional sense, preferring a collaborative approach. She views her role as more that of an ‘editor’ who facilitates her design team to shape the work they create. She’s interested in generating “different lines of thinking” and letting her designers form their own initial interpretations and solutions. As she tells DbyW: “Design is a kind of authorship… I want my designers to write their own version of the story as opposed to getting them to edit my story.” She sees the roles of designer and design lead as two sides of the same coin, with empathy and forward thinking being at the heart of a successful team.

In the course of her career Natasha has observed the link between power and gender inequality firsthand. She notes that the further she’s got in her career and the more senior her role, the more likely she is to encounter situations where she faces barriers attributable to her being a woman. With experience she has learnt how to navigate when these situations occur by taking a gender-neutral approach with the aim that she should be defined by her work, not by her gender or ethnicity.

We talked with Natasha to find out more about her experiences as a partner at Pentagram, the projects she and her team are currently working on, what she looks for when hiring new designers and the qualities she believes are key to success in a creative leadership role.

What were your first steps in the design industry? What factors shaped you as a young designer?

NJ: I studied graphic design in school, that was my major. I knew early on that I wanted to be a graphic designer and that it was a career choice. I started doing design internships from my sophomore year onwards and interned throughout my entire undergraduate education, sophomore, junior and senior years. This meant that I had already learned a lot about the practice of design. By the time I graduated I knew how design businesses worked. The first job that I had was as a designer, or as they called it a director, at Sony music.

As you know, Sony music was a very large music corporation. I was designing album covers for CDs, but I quickly realized that I didn’t just want to design album covers—I craved different types of design. So, I left the Sony job in a matter of maybe six months and got a job at Base Design in New York, which at that time was very small. My job was as an additional Junior Designer, which opened the door to working in a multidisciplinary design practice.

I worked at Base for three years and then moved on to another design firm called Two by Four where I worked for a little over three years. In 2008 the economic downturn and I left Two by Four to become a Creative Director at a strategy company called Stone Yahida Partners. That was a very interesting time for me because before joining SY partners I had very little idea about business strategy. I learned a lot there.

At that point I wanted to start my own studio as there wasn’t any design firm or agency that attracted me. Shortly after starting my own practice I was invited by Pentagram New York, to give a talk to the office. The talk went really well and I was invited to join Pentagram as a partner. So that’s my story.

How did you feel when they invited you to be a partner at Pentagram?

I was honored. I was surprised too because although I interned at Pentagram during my last year of school I never imagined that I would join the firm as a partner.

I was a little bit stressed out at that time because I didn’t know how it would change the way that I work. It’s pretty easy to operate on your own because you can keep your overheads down, but once you join a large firm your overheads increase. So, there was a financial concern. But I was very honored of course and I’ve now been there ten years.

Did you have a team and clients in place when you made the move from N Jen Works to Pentagram, or did you find clients as you went along?

Yes, I had a small team of three designers that moved to Pentagram with me. We had to leave a very nice studio in Chinatown, Manhattan. I closed the lease, sold the furniture and just kept our iMacs. We went into Pentagram with just four iMacs and ourselves and started working right away.

The Pentagram business model is unique and that affects how new projects come through the door. As you probably know, Pentagram is a partner structure and each partner has their own reputation. A lot of times projects will come directly to a partner. Given that my practice was still fairly new when I first joined, I really didn’t have a network of clients or an impressive portfolio. It took me about four years to accumulate work, one project at a time. As you know, some projects turn out better than others, some projects fail. It took four or five years for me to feel more comfortable about the body of work that I had created during my time at Pentagram.

“As you know, some projects turn out better than others, some projects fail. It took four or five years for me to feel more comfortable about the body of work that I had created during my time at Pentagram.”

So, you’ll get some projects coming specifically for a particular partner, but you get some projects coming in where it’s not a given who’s going to work on it?

That’s right.

How did you find that? Because then perhaps you’ve got less control over the type of projects that you take on, or did you find it gave you more freedom to be creative?

I knew two things. Firstly, I knew that I needed to build a body work regardless of what that body of work may be. Because you don’t really know until you look back at a body of work what type of projects you enjoy. So, I knew that I needed to do that. And I also knew that no project was too small. I needed to take on pretty much everything that came my way. So, regarding having the issue of control, it did feel that I was in a kind of survival mode at first. I wasn’t really curating the projects I took on because I wasn’t in a position to do that as yet.

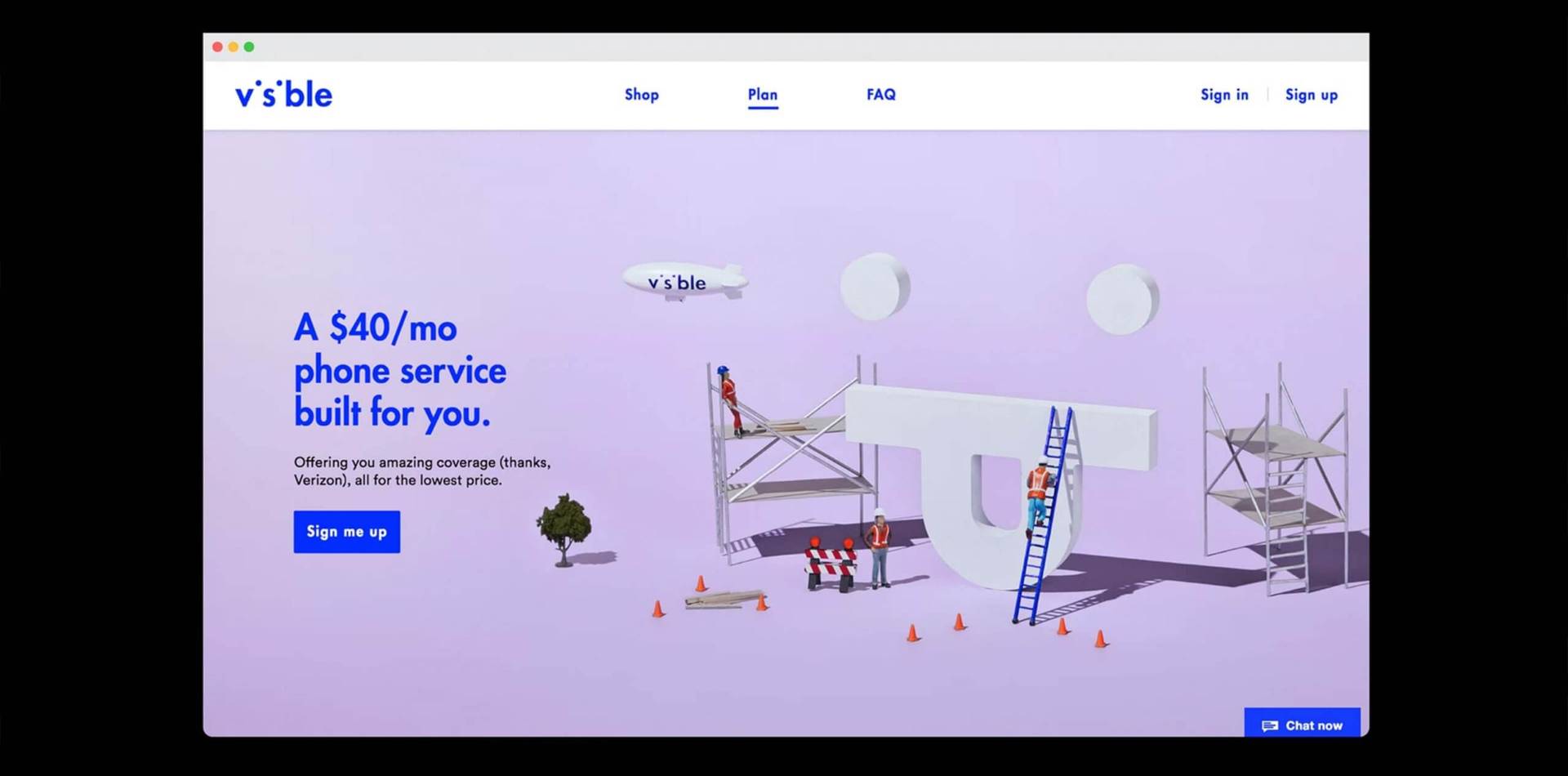

That was how it went for the first few years. For example, I started to accumulate experience and projects in technology and now five years down the road I’ve just started to feel that I have a better understanding of this sector. I have a body of work to prove it. I know the language of this sector, and I work with tech companies a lot more comfortably. And again, that’s something that you can’t expedite, you really need to spend the time and have the diligence and the commitment to learn that.

Do you have a specialism and is there a sector that you like to work with?

I don’t say that we specialize in anything because my feeling is that once you specialize in something, you can do certain things a lot better, but at the same time you’re closing doors on other things that may bring other opportunities. So, I always hesitate to say that I specialize but I admit that I’m very interested in a couple of things. I’m interested in technology in a very general sense. I’m interested in how it changes the way that we behave, the way we interact with one another and the way that we consume, be it consuming physical goods or consuming information, which is a really big part of our lives right now. How do we shop and how do we relate to one another? These are interesting issues that have societal and behavioral impacts.

“I don’t say that we specialize in anything because my feeling is that once you specialize in something, you can do certain things a lot better, but at the same time you’re closing doors on other things that may bring other opportunities.”

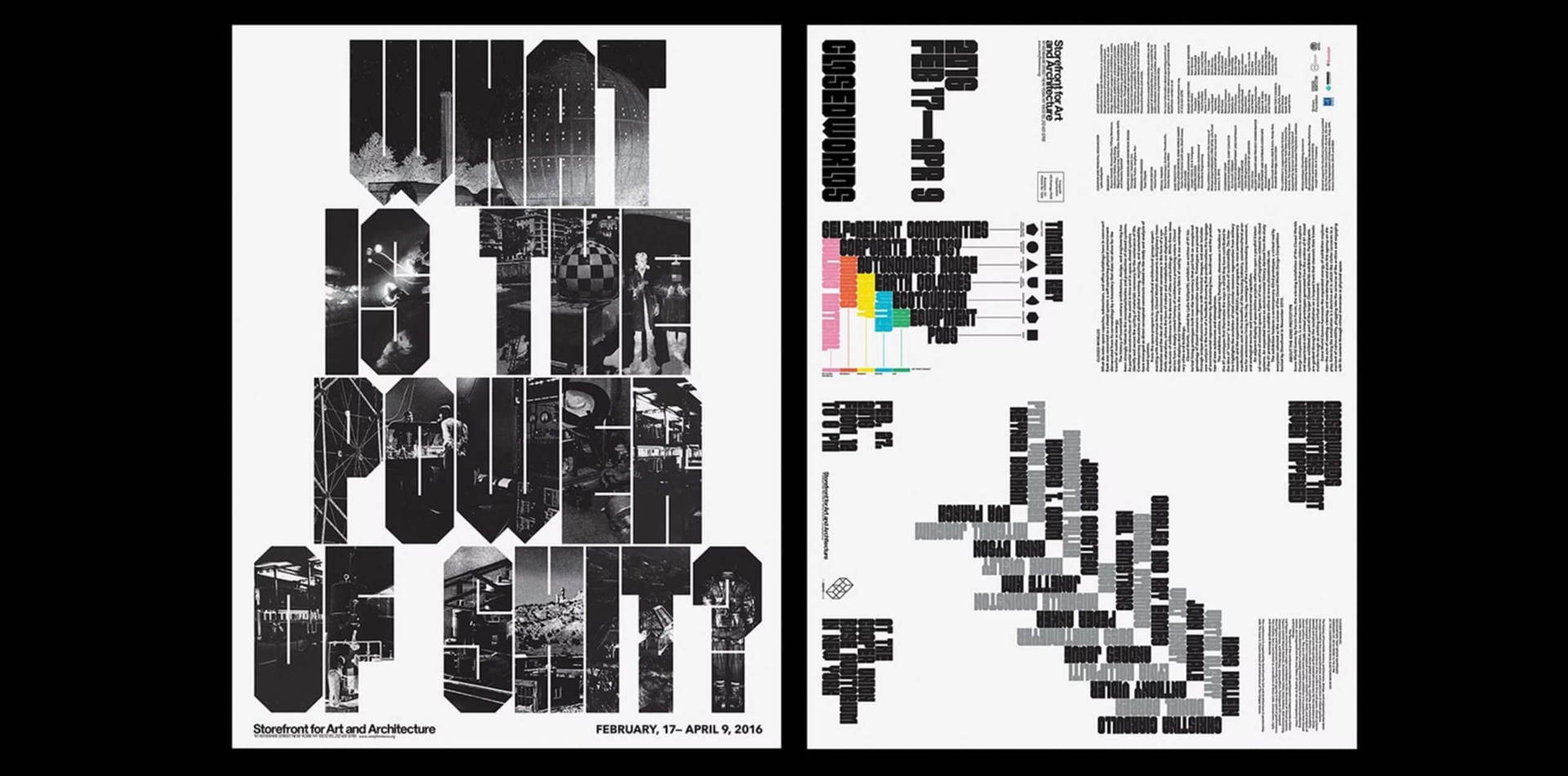

I have also always been interested in art and culture. Art encompasses a pretty broad area for me. It can mean fine art or museums, but you can say that anything that has an artistic idea behind it can be categorized as art. I’m always interested in art and cultural institutions but there’s stuff in between that’s very hard to categorize. I like these blurry boundaries between things, but the intersection between art and technologies is really where my heart is.

How big is your team at Pentagram and how many people do you manage?

My team is always about eight to twelve people. I would say that ten is the average size. I would say 80 to 90% is creative and the rest is project management.

What do you enjoy most about managing a team or running a studio within Pentagram?

I don’t like the term managing. I try not to think about my role as a manager, even though I am a manager. I tend to think of it as collaboration and how I may help my team edit and shape their work. My role is more that of an editor. I enjoy the role of editor and co-designer a lot more than thinking of myself as a manager.

“I don’t like the term managing. I try not to think about my role as a manager… I tend to think of it as collaboration and how I may help my team edit and shape their work.”

How much design and/or creative direction do you get to do in your working day?

Well, it really depends. I do have my own way of working. I start out a project without giving my team any direction whatsoever because I want them to explore what’s in their own heads first. Once you start giving people directions, they tend to stop thinking or they instantly start following your line of thinking. I’m interested in different lines of thinking.

There are projects where designers hit a wall. As a group they don’t feel like they can move on in any meaningful way, if that occurs, then I will come in with more direction. I always hesitate to do that and we don’t get to that point very often. Usually, my designers find their own ways to interpret a brief. Design is a kind of authorship. I want my designers to write their own version of the story as opposed to me giving them the story and getting them to edit it.

During your career have you faced any particular challenges as a woman?

I can speak only from personal experience. I can only speculate because I don’t have real evidence to say that I’m rejected in this situation or that on account of my gender. You can get a sense of the overall climate in particular situations. If it’s a male dominated environment where you’re the only woman, you have to try to win the approval of this room full of men. And then if you’re rejected very brutally, or if you’re humiliated in front of a group, then you can speculate that it is because of gender. I have experienced that several times in my career with varying degrees of severity. From small rejections that may happen more often, but which are so light that you can figure out how to navigate them, to really severe setbacks where you are literally humiliated in front of a large group of people and have to figure out how to exit the situation gracefully. I have experienced that.

I always tell myself that I don’t want to be defined by my gender or by my ethnicity. I want to be defined by my work and that’s always how I see myself. If gender discrimination issues arise, then I put on my helmet and armor to metaphorically fight. But I don’t enter a situation with the mindset that because I’m a woman I will be disadvantaged.

“I always tell myself that I don’t want to be defined by my gender or by my ethnicity. I want to be defined by my work and that’s always how I see myself.”

Did you ever lack confidence when you started out?

Absolutely! I was petrified when I had to present to clients on my own. Early on, I remember that I was taking a train from New York up to MIT to present to the MIT architecture department. The train ride was maybe four and a half hours and I vomited because I was just so nervous. That was 2010, 12 years ago. So, like I said, confidence is not something that we are born with. You just have to confront lack of confidence, deal with it, and build it over time. You get better and stronger through experience.

Did you find it an easy transition from being a designer to leading a team?

For me these two somewhat different roles are actually two sides of the same coin because you have to think like a designer in both. You think very specifically about projects and about the problems that you’re trying to solve, which have both conceptual and formal implications. You’ve got to think in the creative realm, but at the same time you think about it in terms of the business, the culture, the team, hiring etc. The two things go together because you need to get the right people in order to do the type of work you want. And you need to have the right type of work to attract the right people and build the right team.

Do you think things have improved in terms of gender equality since you first started in the design industry?

That’s an interesting question. I think there’s no chronology to gender discrimination or any sort of discrimination, meaning that discrimination or inequality is omnipresent. So, getting older does not mean that you experience less discrimination. It is actually quite the contrary because as you get older, your responsibilities are greater and your role often becomes more senior. I find that the older I get the better antenna I have for noticing gender inequality. When I was in my twenties, I had a good time with peers of my own age. We all created together and there wasn’t much hierarchy or power plays. Once power enters the conversation, then gender equality becomes an issue.

“I think there’s no chronology to gender discrimination or any sort of discrimination, meaning that discrimination or inequality is omnipresent. So, getting older does not mean that you experience less discrimination. It is actually quite the contrary because as you get older, your responsibilities are greater and your role often becomes more senior.”

I acknowledge that today there is a lot more effort to address gender inequality and I think that’s great. That’s a direction that we should continue in, but I think that discrimination is going to stay in different shapes and forms. There’s no way that we can eliminate it because we’re human beings after all. However, as a society and as a profession, we should be very aware of issues of power and inequality.

The statistics are very revealing about gender inequality in the design industry. But it is obviously linked to society as a whole. Do you think we need to change the way society is structured to make a fundamental change?

Yeah, totally. You know, like the way we work, working hours and the number of days we work. The present arrangements are basically structured for men. There’s no acknowledgment that women may have children, may become pregnant or become a mother. Often women have to stay home to take care of children at the same time as doing their job. As women we have to figure out what is best for ourselves, what actually works for us. I think that everybody is different, so we have to be a little selfish and set our own parameters.

Are there any projects that you’re working on at the moment that you could talk about, anything that you have particularly enjoyed?

I can’t mention names because the projects are not yet in the market, but we’ve been working on several crypto, Web 3 technology brands. Those are interesting and exciting because as you know, this is a really hot topic right now. We hear about how blockchain may democratize access to anything and that is still very much a big question. We also hear about cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin, and so on… Although blockchain has been around for more than 10 years, it seems that we are on the cusp of it becoming a more widely known technology. Whether it’s necessary and it’s going to replace the current web 2.0, we don’t know yet, but it’s very exciting to be engaged in what I would call a very large experiment that has millions of people participating in it right now.

I’m very excited about this space but I’m also very concerned about a lot of what I would call ‘bad actors’ in the space. You hear a lot about scams, about the volatility of cryptos and how people have lost money. These are all the byproducts of something that is happening really fast and is as yet unregulated, so I’m very interested in what we, as graphic designers, can do to make it better and shape the space.

How long does an average project last or are they all different?

It depends. I would say most branding projects last about like five to six months, starting from research to interview, to brand positioning, messaging, identity design, and then design development. But sometimes a project can take a lot longer, say like a year if the client is large and you need to work through different groups of things to really figure out what the totality will be.

What are the most important qualities for being successful in a design lead role as opposed to being a designer?

That’s an interesting question. Empathy, I think, first of all, I know that empathy is a word that’s bandied around a lot in leadership conversations, but it is a quality that is really critical because you need to relate to people and how they feel. I also think that having a kind of forward ambition is important because you need that as a torch to lead by. As a north star to actually lead the team. Otherwise, you have no clear direction. That sort of forward-thinking ambition functions as a glue that can bond people together. You need your team to be as like-minded and focused as you .

“Empathy, I think, first of all, I know that empathy is a word that’s bandied around a lot in leadership conversations, but it is a quality that is really critical because you need to relate to people and how they feel.”

When hiring new designers for your team is there anything specific that you look for?

Well, the first thing’s always the quality of the work. You want to see talent, creativity and craft. These things are very important, but there’s also a sense of curiosity. I think that’s critical in designers Having a passion to solve problems, that I think is another critical component.

Do you have any advice for women and marginalized genders who might be looking to move up to a more senior role or run their own studio?

I would say that the most important thing is to have the dream and the ambition. You’ve got to have that vision and desire in your gut that will propel you to take action, to make your dream happen. And then you need to have the commitment and stamina to push towards that dream.

I have always told myself that I’m not defined by my gender or my ethnicity. I’m defined by my work. And also, by the scope of my ambition. Of course, sometimes as you grow your ambition changes, sometimes it’s bigger, sometimes it’s smaller. That’s totally okay. But I have it very clearly in my mind that I’m defined by that, and not by the fact that I’m Asian. We don’t need special treatment because of our gender and/or our ethnicity because we’re just as good as everyone else. That’s what I tell myself. But should we work to help elevate others? Absolutely. But that’s different from doing it out of sympathy if you know what I mean? We do it out of a shared human spirit. That is, we want everybody to get better. We’re lifting everybody up.

“I would say that the most important thing is to have the dream and the ambition. You’ve got to have that vision and desire in your gut that will propel you to take action, to make your dream happen.”

What advice would you have for emerging designers around gaining confidence at that early stages in their career?

Well, confidence building is very much like building muscles. You are not born with it. You have to exercise and practice over and over and over again. And each time you practice it is not always a pleasant experience, it’s like trying to lift very heavy weights. You’ve got to just go through it. It can be a little bit painful, but need to practice and put yourself out there, present, give talks to people or teach for example. The more you do it, the more confidence you will build over time. So, it really is much like building muscle.